- Home

- Celia Bryce

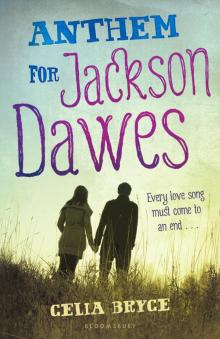

Anthem for Jackson Dawes

Anthem for Jackson Dawes Read online

Contents

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

My Inspiration for Anthem for Jackson Dawes

Acknowledgements

For

Deanna Hall

1971–1979

and

Vaila Mae Harvey

1991–2008

Jackson Dawes

He’s as tall as doors,

standing

in his

battered old hat,

singing his

battered old

songs,

slapping his fingers down the length of the stand

like an upright bass.

Badum, dum, dum, dum;

badum, dum, dum, dum.

His hips swing gently,

his head nods,

his smile is wide, big

as

the sun,

as if this is just

any other day, as if the world

can’t get any better,

as if the future

is brighter

than

stars.

Megan Bright, Megan Silver,

he sings in that way of his.

Megan Bright, Megan Silver…

One

‘Now you know what I think of hospitals, so you can ring me any hour of the day or night.’

Grandad’s voice seemed a long way off, making him sound even older than he was, making him sound as if he was on another planet instead of at the other end of a telephone.

It was Megan’s first day in. ‘Yes, I know,’ she said, trying to sound brave, wanting everything to be better without having to be in hospital. She followed Mum through the double doors on to the ward, and stopped dead.

A baby ward?

That couldn’t possibly be right.

But it was.

There were babies and signs of babies everywhere. Toys being banged. Something rattling. Another thing chiming. Whirring. Squeaking. Somewhere off to the right there was a baby crying.

Just ahead a small child driving a plastic car headed off to the left. The horn beeped. An adult followed in deep conversation with a nurse.

Grandad was still talking, telling her not to worry, but Megan couldn’t answer.

Where were the other patients? People like her? People her age?

She wasn’t a baby or a toddler. She was almost fourteen!

Why had they put her here? How could they?

Text Gemma. As soon as possible. She’d know the answers. That’s what best friends were for, wasn’t it? To calm you down, talk you through things. Though with Gemma it was more a case of hugging you through things!

Dad liked Gemma. She didn’t waste words. Not like some of Megan’s friends. The Twins, for example, who would always use a hundred words when one was enough.

With Gemma it would be a or a and that would sum it all up.

Yes.

Text Gemma. Even she would have something to say about being put on a baby ward.

Grandad was still trying to be cheerful. ‘They won’t let me loose on a bus, so I can’t come down … But if there’s anything bothering you, lass, just tell them you have to call me. Tell them I’m the oldest man in the village, which means I know more than they do.’

Megan laughed because that’s what he’d have wanted, but Grandad wasn’t finished.

‘In fact, if they need a hand with anything … washers for taps, spanners, wrenches, anything to do with plumbing …’ he said.

‘They probably have people to do things like that,’ Megan interrupted, determined to keep the shake out of her voice. It wasn’t easy. She could hear babies crying. She could hear the whine of toddlers. It occurred to her that she probably wasn’t supposed to be using her mobile. It might interfere with things. Like on aeroplanes. If anyone noticed, they might take it off her. She clamped it closer to her ear. No way. Not before she reached Gemma. Oh, hurry up, Grandad. Ring off. Shut up.

But no. He was still trying to make it all turn out right, trying to fix things the way he always had when he ran his hardware shop.

He could fix just about anything, could Grandad.

‘Well then, you know where I am.’ He sounded even further away. ‘But it’ll be fine, you’ll see, sure as eggs is eggs. Bye for now, Pet Lamb.’

Eggs is eggs. Yeah. Well.

It was horrible. The whole thing. Having cancer was bad enough, since it wouldn’t go away on its own, but really? A baby ward?

And the hospital was miles away from home. It meant that Mum had a lot of driving to do in the city. She hated city traffic and you couldn’t ever find a place in the hospital car park.

It was just going to be too difficult, the whole thing.

‘Well,’ Mum said, ‘this isn’t bad, is it?’

Megan twisted her face. ‘It’s not good.’

‘Of course … obviously it’s not good, having to be here, but when you’re poorly …’

‘Yes, I know, but …’ Megan stopped. But what? Exactly? What did it matter if the place was full of babies, full of toddlers? She had cancer and had to have it sorted out.

Yet it did matter.

Somehow it mattered.

‘Never mind,’ Mum said, keeping bright, like the colours around them both, on the walls, on the ceiling, wherever you looked. Nothing stayed too terrible for long according to Mum. ‘There’ll be lots to tell Dad when he rings. He’ll want to know what’s what.’ Then her voice changed, the cheeriness disappearing, as if it was too hard to keep it going for ever. Like balloons at a party. They always went down, eventually. ‘I wish …’

Megan knew what was coming. Her stomach tightened as if she’d just swallowed a bowl of cement. She didn’t want to hear it. ‘Dad doesn’t need to be here. I’ve got you.’ Trying to be cheerful. ‘And I’ve got Grandad. I’ll be all right.’

Mum sighed. ‘Yes, you’ve got me and Grandad.’ She managed a small laugh. ‘And he’s threatened to phone every day. Twice a day if he has to. I feel sorry for the nurses. He’ll be checking up on them, just watch.’ She shook her head. ‘As if he knows the first thing about hospitals. About this sort of place, anyway.’

A curly-haired toddler came racing towards them on his bottom. He was being chased by his curly-haired brother who picked him up with a struggle. Then his curly-haired mother appeared, her cheeks pink, a deep frown on her face.

‘Careful with him, Dylan, please!’

The toddler giggled as if this was the funniest thing ever. His mother smiled a tight kind of smile.

‘Welcome to the madhouse,’ she said, scooping up her son, who whooped in delight. She gave Megan a sympathetic look. ‘Don’t worry, love, we won’t be here for too much longer! Peace does happen sometimes.’

‘Whoa!’ Something from behind hurtled into her, big hands gripping her shoulders. ‘Sorry!’ The something was a boy, tall as anything, in a big T-shirt and baggy jeans. ‘I’m trying to see how fast you can push one of these. Important scientific research. See ya!’

Sidestepping Megan and her mother, he steamed on ahead with his drip stand. There were four bags of fluid hanging from it and tubes like spaghetti tumbling into two blue boxes clamped on to the stand.

‘Oh … well …’ Mum looked vague. ‘Research.’

‘I don’t think so,’ Megan said, ‘an

d I don’t need any more help to make me dizzy. How stupid is he?’ She took Mum’s arm because now she was feeling quite wobbly. ‘Oh no. He’s back.’

Sure enough, the boy was heading their way once more.

‘Hey, you’re not a baby!’ The drip stand squeaked as he pushed it along. He gave her a huge grin. ‘You’re normal!’

What did he expect, a Martian?

‘Say hello, love. Where’s your manners?’ Mum whispered, nudging her.

‘He’s just collided into me,’ Megan muttered. ‘Where’re his?’

The boy was checking her out as if he’d never seen a girl before. Or had seen too many, and knew just where to look. Scowling, Megan folded her arms, wishing Mum had made her put on a thicker top.

‘We’re new here,’ Mum said, bright as light bulbs. ‘Don’t know where we’re going really, just told to … you know … turn up!’ She threw her arm around Megan’s shoulder and squeezed, as if this was the first day at Butlin’s.

Shrugging her off, Megan looked at the boy, tall as doors, taller even, with a hat pulled down low like a gangster in a film. His eyes were dancing. He was laughing at her. Probably not even on this ward and just here to gloat. Well, let him.

The boy was just about to say something when two little girls came down the corridor, arms linked, heads close, talking giggly secrets. They stopped and gazed, sparkle-eyed, first at the boy, then at Megan.

‘Jackson,’ said one, her voice high-pitched, her face alive with excitement, ‘got a new girlfriend?’

He shook his head, tutted. ‘Becky, Becky, Becky! Give us a high five,’ he said. They high-fived. ‘Who’s your friend?’

‘Laura.’

‘Well, here’s one for you too, Laura.’ He high-fived the other girl. More giggles rang along the corridor.

Was he playing with nine-year-olds? Sixteen, seventeen, maybe, and hanging out with nine-year-olds? Megan picked at a speck of fluff on her sleeve, but it wouldn’t come off. Mum was smiling so much her cheeks were two red balls.

They should be unpacking. The nurses might be waiting or a doctor. Someone should be told she’d arrived. Yet there they were still in the corridor, with all its cartoons and him standing in the middle of it, the star of the show.

Megan pressed into the wall, like a shadow.

More giggles behind hands clamped to mouths. The boy looked down at the girls like a school prefect, the girls looked back up expectantly, as if this had all happened before, as if they knew what was coming next, as if it was all just a big game.

‘Will you tell us a spooky story, Jackson? Laura wants to hear one. Will you?’

Megan rolled her eyes.

‘Not right now. Go on, Becky. Aren’t you meant to be visiting your brother? Isn’t that why you’re here …?’

The girls looked at each other as if they’d just remembered. ‘Whoops! OK. See you later!’ Overcome with laughter, they bumped along the walls towards the main ward. Jackson shook his head then turned back to Megan, checking her out once more. She looked the other way.

‘Quite a fan club you’ve got there!’ Mum said, giggling like a girl, as if she wanted to be part of it too.

The boy laughed. ‘Something like that.’

Megan stuffed her hands into her pockets and examined a picture on the wall. It was a fat elephant. Flying. It had three pink toenails on each foot.

There was a tap on her shoulder. It was the boy. ‘So, what’s your name?’ he asked.

Megan turned to face him, but didn’t answer.

‘Oooh, she’s lost her tongue all of a sudden. This is Megan and I’m her mother. High five, Jackson!’

‘Mum! Don’t we have to go …? I’ll need to sign in or something.’

‘Yes …’ Mum was still smiling, still gazing at Jackson.

‘They do need to know I’m here, don’t they?’ What was it about this boy that had everyone going all gooey?

A movement in the corridor made them turn.

‘Uh-oh! Sister Brewster …’

Coming towards them was a tall woman, with hair like wire. It was short and grey and made her look like a head mistress. Under her arm was a bundle of folders. She stopped and turned startlingly blue eyes to Jackson, who was suddenly silenced. Megan shifted her gaze back to the elephant’s pink toenails, trying to stifle a laugh. Not such a big star now.

‘Jackson … at least let the girl settle in. She’s not had a chance to catch her breath!’

Megan sensed that Sister Brewster wouldn’t be messed with. Jackson obviously knew it too. With a sheepish shrug, he took off his hat and gave a slight bow. He was completely bald. Mum’s mouth fell open.

‘Polished it this morning, just for you coming in,’ he said, grinning and putting his hat back on.

‘Yes. Thank you, Jackson. Show’s over.’ Sister Brewster moved to one side to let him past. ‘You have a visitor.’

Jackson gave them all a wide grin. ‘See you later,’ he said, striding down the corridor, hips swinging, long legs almost bouncing him away and his drip stand trundling along beside him.

Sister Brewster shook her head and sighed. ‘Completely starved of company since he got here.’

As he headed away, a door swung open and out stepped a small lady wearing a black hat with a feather, a thick yellow coat and a face like thunder. She stood with her hands on her hips, round as a dumpling.

‘Jackson? You come right here, boy, disturbing the peace like some hooligan.’ Her voice was loud and gravelly, not to be ignored.

Jackson stopped and turned back to face Megan. ‘Meet my mother …’ he said. ‘I don’t know how she does that. Showing up at just the wrong time. How does she do that?’

Megan shrugged a haven’t-a-clue kind of shrug. Serves him right. Big-head.

‘Can’t let a poor girl even find her room without you getting in the way. Come here this second, boy.’

‘All right, all right!’

Jackson’s mother stood by the door, waiting until he was back in the room. She marched in after him.

‘That boy,’ Mum said, ‘is just beautiful. He’s like an ebony statue. And that smile … it just never stops. Isn’t he lovely …?’

‘That boy,’ Sister Brewster said, ‘could use a distraction, and I think he’s found one.’ She nodded meaningfully at Megan.

No way. No. Way.

Megan hadn’t liked the consultant’s room. It was down in Outpatients and it was where they told her she had cancer. It wasn’t like a real doctor’s room. Her own doctor had pictures of his children on the wall. Three boys, all the same age. A nightmare in triplicate, he called them.

He had funny little toys on his desk to keep little patients amused. She remembered going there when she was small; she remembered the tiny monkey which crawled up his stethoscope, or it would have done if it was real. She remembered thinking that he was the nicest doctor in the world. On the wall above his examination couch he had an enormous photograph of some mountains, all covered in snow, like a ski resort. He looked as if he was always just about to go on holiday, her own doctor. Cheerful, full of fun.

The consultant was about as much fun as a carton of warm milk. He had half-moon glasses and when he smiled, which wasn’t very often, he looked like a frog. His room had bare walls and too many doors. He had a nurse whose mouth looked too small for her face. She came in one of the doors with a pile of folders, which she put on his desk, then she disappeared through another door. Megan had no idea where they all led to. She’d come in from the Red Area waiting room, through the sick children’s entrance. Everyone who came through that door was supposed to be poorly, whether they felt it or not.

Maybe it was to do with all of this that Megan laughed until she almost wet herself, when he said she had a tumour and the tumour was cancer. It was a mistake, obviously. She didn’t feel ill for a start.

She looked at Mum and Dad to see if they realised that it was all a mistake too, but they just sat quietly, side by side, like those things Gran

dad had to stop his books falling over. Bookends, he called them.

She hadn’t been ill, just dizzy at times. A bit wobbly. How could it be cancer? It was stupid. She would just go home and forget about it. Easy-peasy.

Anyway, what did he know?

The consultant twiddled with his pen until she’d finished laughing, but just as he was about to say something, Megan fired one question after another at him, as if she’d been saving them up for weeks and had to get them all out. She left no space for answers. Would she still be able to play football? And go to the ice rink? Would she still be able to go to the cinema with her friends? Would she still be able to go shopping? What about school? Would the tumour go away by itself? Why had it happened?

At last the questions dried up. All of that activity made her tired. Megan slumped back in the chair and could think of nothing else to say or do.

She noticed how the consultant was examining the blotter on his desk.

She noticed how still Mum and Dad were, like statues, how they were holding hands.

‘I realise it’s a shock to be told this,’ the consultant said at last, ‘and I’m very sorry that the tests couldn’t have given better news.’ He flipped open a folder, which must have been Megan’s. There seemed to be a lot of pages. A lot of tests. ‘But now that we know, and we’re sure about it, we can think about how to treat you.’

Treat me? With chocolate? Ice cream? New clothes? Don’t think so, somehow.

‘I think what we’ll do is try some chemotherapy and that should make it easier to remove.’

‘How do you do that?’ Megan asked. Her mind had gone completely blank. ‘How do you remove a tumour?’

The consultant seemed taken aback. ‘We do an operation,’ he said.

‘You mean, cut my head open?’

‘Yes, Megan. That’s exactly what I mean.’

But why, when she didn’t feel ill? Why didn’t Frog-Man get his head cut open? Check there was a brain in there, because he’d got it all wrong. He must be thinking about some other patient. Probably that stupid nurse with the little mouth had given him the wrong file. There was probably another Megan Bright. That’s what had happened.

Easy-peasy. Lemon-squeezy. And yet, she began to shiver. It wasn’t cold in the room, but she was trembling all over. Someone took her hand. It was Dad. She had to check, because everything was feeling very strange now. She felt like a foreigner, someone who didn’t understand the language, someone who’d do anything to hear something familiar.

Anthem for Jackson Dawes

Anthem for Jackson Dawes